Qingming Festival - Steps, Traditions And Legends

Qingming Festival - Steps, Traditions And Legends

Qingming Festival, or Tomb-Sweeping Festival in English, is a celebration observed by many ethnic Chinese groups in countries such as China, Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Macau, Thailand, and Malaysia. It normally falls during the first week of April in the Gregorian calendar, or the first day of the fifth solar term of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar.

As the name implies, families would visit the graves of their departed loved ones and clean them. The tradition itself has Confucian roots, which emphasizes the importance of filial piety and social harmony - a value shared by many modern Chinese cultures still.

History says that the practice has been kept for over 2500 years, marking its significance in Chinese culture. During the Qingming Festival, in addition to cleaning the gravesites, families would also pray to the spirits of their ancestors and burn incense and joss paper, as well as put up food offerings.

History of Qingming Festival

According to legend, the Chinese tomb-sweeping festival first originated from the Cold Food or Hanshi Festival, which commemorated Jie Zitui, a nobleman of Jin during the Spring and Autumn Period. During the Li Ji Unrest, Jie followed his master Prince Chong’er into exile among the Di tribes around China. Jie was such a magnanimous subordinate that it was said that he even cut flesh from his own thigh to provide his lord with soup on one occasion. In 636 BCE, Jin was invaded by Duke Mu of Qin and Chong’er was subsequently enthroned as its duke. However, the blessings did not extend to Jie, who eventually retired into the forest around Mount Mian to live with his mother. After attempts to locate Jie failed, Chong’er ordered his men to set the forest ablaze to force him out. When Jie and his mother died, Chong’er was overcome with regret and erected a temple in his name, banning the lighting of fires for as long as a month in the depths of winter. However, this practice had a negative impact on the livelihoods of the people, and rulers sought to ban it for centuries, albeit in vain. Eventually, a compromise was made to limit the ritual to 3 days during the Qingming solar term in mid-spring.

The present Qingming festival owes its significance to Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, who was unhappy about the lavish celebrations held by the wealthy in honor of their ancestors, and declared that such practices can only be held once a year during Qingming.

The 24 solar terms. Source: JinPaper

As mentioned, Qingming falls on the first day of the fifth solar term of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. A solar term marks a single period in a year which matches a specific astronomical event or coincides with some kind of natural phenomenon. Each point is spaced 15 degrees apart along the ecliptic, and are crucial indicators for the agrarian societies of the past to stay synchronized with the seasons.

The first ever solar term is Dongzhi (Winter Solstice), coined by Duke Dan of Zhou, who attempted to locate the geological center of the Western Zhou dynasty by measuring the length of the sun’s shadow on an ancient timekeeper instrument known as Tu Gui (土圭). Four terms of seasons were then set, which evolved into eight, and ultimately, the twenty-four solar terms were formally recognized in the Chinese calendar in the book Taichu Calendar in 104 BC.

Why do Chinese celebrate the Qingming Festival?

The Qingming festival is a day in which Chinese visit their ancestral tombs to perform groundskeeping and maintenance. It was legislated by the Emperors of old who built majestic tombs to honor their predecessors, and has been practiced by the Chinese people as a whole for thousands of years regardless of social status or wealth. As it coincides with Confucian values of filial piety, the Chinese believe that tomb sweeping is a show of respect to their ancestors, as well as a way to remember them always.

The belief in the afterlife is another concept that has been uniquely Chinese for a long time, and in addition to cleaning the gravesites, the Qingming festival helps to connect the departed with the living. Some families see it as a way to talk to their departed loved ones about what has happened since the last time they visited, much like how we would catch up with our distant relatives during Chinese New Year.

Some also believe that continued observance helps gain the blessings of their ancestors for the future, and modern farmers especially view this as an important practice to ensure fruitful harvests in the coming months.

When to celebrate the Qingming Festival?

In the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, the Qingming festival falls on the fifth solar term. This coincides with the 15th day after the Spring Equinox, making it fall on either 4, 5, or 6 April of any given year according to the Gregorian calendar. The occasion usually takes up the whole day, starting from the early morning to late afternoon. While it isn’t formally recognized in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, it became legislated as a public holiday in mainland China as of 2008, and up until recently, Taiwan as well.

The holiday is also often seen as a mark of remembrance for people of exemplary nature who passed away. Some notable examples include the April Fifth Movement and the Tiananmen Incident, which took place during the Qingming period.

How do the Chinese celebrate the Qingming Festival?

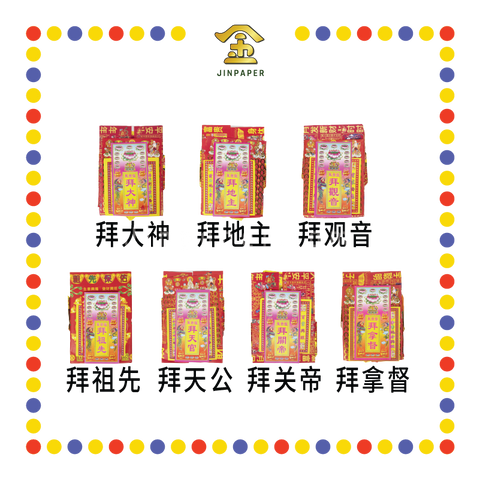

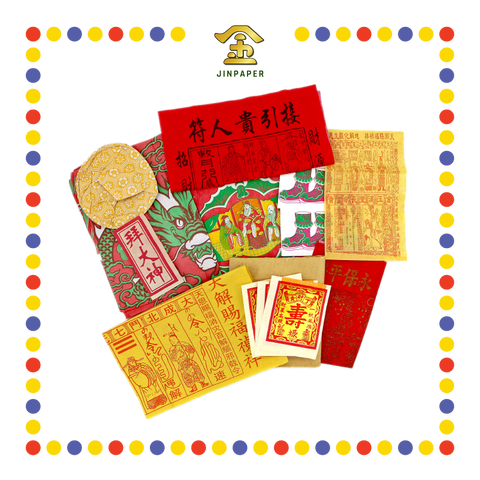

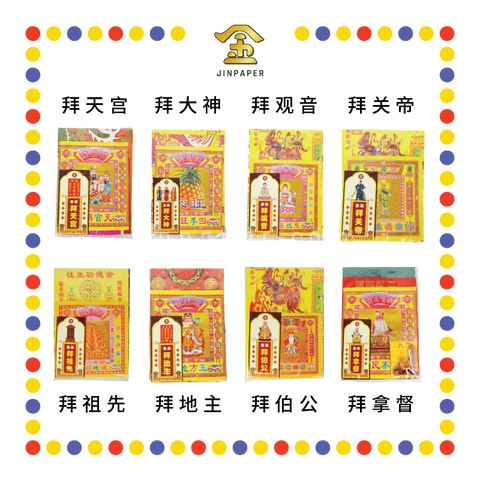

The Qingming festival is often seen as a family obligation instead of a regular celebration. Hence, family members both young and old almost always show up in full attendance. The standard rituals include kneeling in front of the grave to pray, burning of joss sticks and sometimes joss paper, sweeping the tombs, and putting up food offerings. It is also fairly common to pour libations of either tea or wine in memory of the ancestor, depending on their preferences in life.

In the past, some not so common practices include the carrying of willow or pomegranate branches on the person during Qingming or hanging them on the gates or front doors of the person’s home. This is because pomegranate and willow branches are seen as religious symbols of ritual purity, and are thus capable of warding off unappeased spirits, as well as evil spirits that may be wandering the mortal realm during Qingming.

Traditionally, after performing their family or clan duties on the burial site, families would engage in feasts and merrymaking before returning to the fields. Singing and dancing was a common sight to behold, and many young adults would use this opportunity to start courting one another. Besides which, some would also fly kites in the shapes of animals or certain characters from the opera, as well as carry flowers in lieu of incense and firecrackers. Cockfights were also fairly popular at the time.

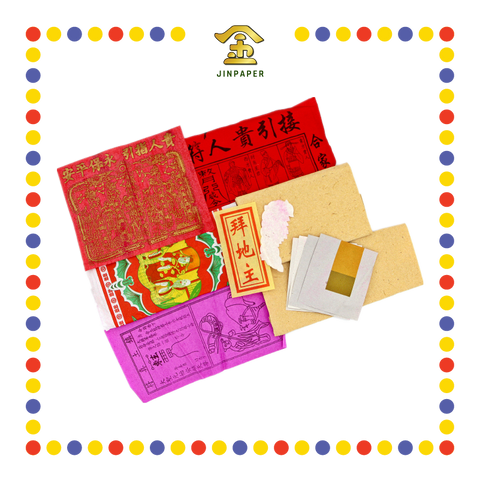

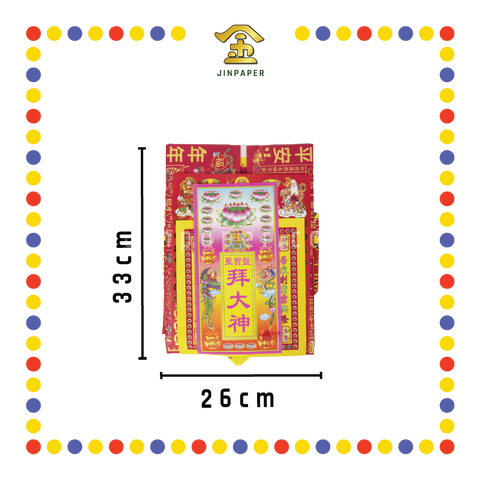

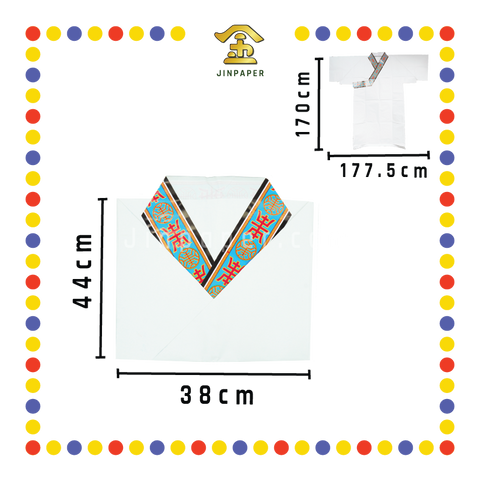

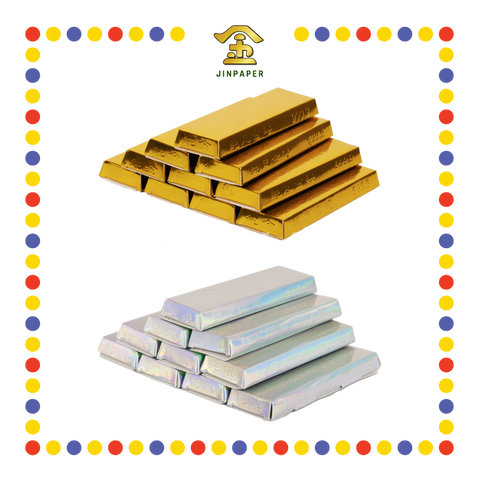

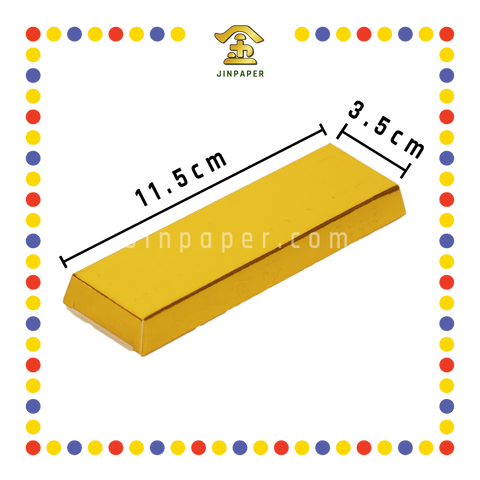

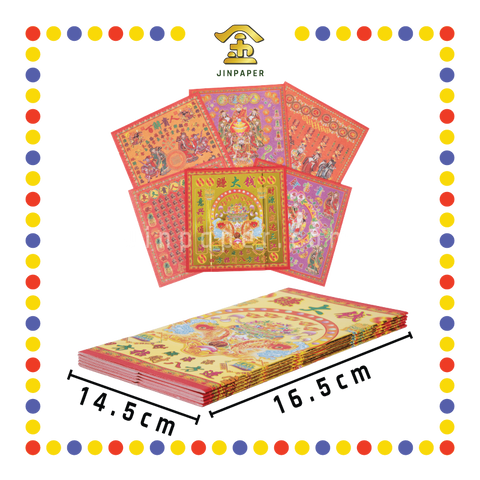

An interesting aspect of the afterlife in Chinese culture is the belief that departed souls would still have need for material wealth, and as such, some families opt to burn not only joss paper (spirit money), but also paper models of material goods such as houses, cars, phones, and even servants. This practice normally precedes everything else, following which the family members would then kowtow before the grave of their ancestors any number between 3 to 9 times, depending on their personal family beliefs and rituals. The act of kowtowing is typically performed by order of patriarchal seniority within the family. Once the obligatory rituals are out of the way, the family can proceed to feast on the food and drink they have brought with them for the worship at either the site itself or any nearby resting area.

In countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, some practices can be dated as far back as the Qing and Ming dynasties, as these places were not affected by the Cultural Revolution that took place in mainland China. Families would perform the basic cleaning and incense offering rituals at the tomb site, and sometimes pray to their forefathers who had come from the mainland in temples or home altars as well. As it is not formally recognized as a public holiday for overseas Chinese, families would opt to visit on the weekend closest to the date instead. Ancient customs state that grave site veneration is only permissible 10 days before and after the actual date of the Qingming festival, and should visit on the day itself not be possible, it is highly encouraged to do it before the festival. In Malaysia and Singapore, Qingming observation starts in the early morning with prayers to our Chinese forefathers at home altars, followed by visits to the graves of close relatives in the country. Some even go so far as to visit the graves of their ancestors in mainland China as a show of filial piety.

Chinese families visit the graves of departed loved ones to pay their respects during Qingming festival at Kwong Tong cemetery in Kuala Lumpur. Source: JinPaper

Conclusion

To end this on a lighter note, the Qingming festival is one tradition in which the Confucian values of respecting one’s elders and appreciating familial bonds, both integral aspects of traditional Chinese culture, are expressly displayed, despite being an occasion in which the dead are celebrated. While the rituals are not too complex, it is nonetheless one practice that is steeped in history. Perhaps that is why it has endured for thousands of years, and may it continue to live on for thousands more.

For more news and information on traditional Chinese festivals and rituals, be sure to follow us at JinPaper, Malaysia’s number one supplier for Chinese praying materials. If you’d like us to feature something new or would like to highlight something that we missed, feel free to drop a comment below!