Malaysia Chinese New Year - Culture, Events & Festivals

Malaysia Chinese New Year - Culture, Events & Festivals

Let us paint you a picture — vivid-red decorations and knick-knacks deck the walls, classic energetic tunes played repeatedly over the speaker, smiling faces of those dearly missed, the explosive crack of fireworks being set off out in the front yard — these are but a few of the typical sceneries you will see during every Chinese New Year.

A cultural focal point for all those of Chinese descent, Chinese New Year, or Lunar New Year, as it may be called, is a worldwide event celebrating the coming of spring, symbolizing new beginnings, and better tidings for the year.

While countries such as Malaysia and Singapore don’t experience such seasonal changes, the sentiment is felt all the same. You might even say that Chinese New Years here are a little more unique, owing to our cultural diversity.

History of Chinese New Year

Like many centuries-old traditions, the Lunar New Year’s origins can be somewhat obscure, owing to contradicting accounts and many ancient records now lost. To the best of our knowledge, the tradition is at least 3500 years old, originating during the Shang dynasty, when people would offer sacrifices in honor of the divine at the beginning or the end of each year.

It wasn’t until much later during the Han dynasty when the date for Chinese New Year was officially set. During this time, the Han people also started the practice of visiting the houses of relatives and friends at the start of the new year. As we enter the Wei and Jin dynasties, we start to see that in addition to the rituals of worship, people began to entertain themselves during Chinese New Year. As described by the Western Jin general Zhou Chu in the article Fengtu Ji, it was common for the populace to visit each other’s houses, bearing gifts and wishing one another a happy new year, reveling in food and wine for the entirety of the night. The article used the word chu xi (除夕) to indicate this time as New Year's Eve, which is still being used to this day.

From a mythological perspective, the tale which explains how Chinese New Year began is one which famously portrays the demonic beast, Nian. Nian is a creature that lives under the sea, or in the mountains. According to legend, it would appear every year during the Spring Festival, devouring villagers, especially children in the middle of the night. One fateful year, as the villagers were hiding from the beast, an old man appeared. He stated to the fearful villagers that he would stay the night and exact revenge on the Nian. The villagers let the old man be. Much to their surprise, the next day came and the old man was still very much alive. It turns out that the old man had put up red papers and set off firecrackers that night. The villagers quickly understood that the Nian was actually afraid of the color red and loud noises. Naturally, this practice became widely adopted by the villagers — they would wear red clothes, put up red lanterns, hang red spring scrolls on doors and windows, and used firecrackers and drums to scare the Nian away come Chinese New Year every year. And after that, the Nian was never seen in the village again.

An illustration of the Nian beast. Source: JinPaper

Why do the Chinese celebrate Chinese New Year?

Like several other ancient cultures in the world, the Chinese people observe two calendars. Aside from the globally-accepted Gregorian calendar, the Chinese also have their own Lunar Calendar. This Lunar Calendar sees the year divided into 24 solar terms — the specific points of the Sun in relation to the Earth’s orbit along the ecliptic. According to the Lunar Calendar, Chinese New Year takes place on the new moon closest to lichun, or the beginning of spring, which is the first solar term of the cycle taking place after the winter solstice. This is often associated with a new year for harvests and a symbol for fresh beginnings.

For a more contemporary take on the celebration, the Chinese New Year is a symbol for inviting good luck and prosperity into the household ahead of the coming year. It is also cause for reuniting with family members that aren’t seen often. Familial bond and good fortune are two key intrinsic values in Chinese culture, and no other event celebrates these two motifs quite as strongly as Chinese New Year.

When to celebrate Chinese New Year?

As briefly mentioned earlier, Chinese New Year always falls on the new moon which is closest to lichun. Translated to the Gregorian calendar, this date can fall anywhere between 21 January and 20 February, depending on the moon’s cycle. The date will also differ depending on the geographic area, owing to varying time zones and different placements of intercalary months.

While most families don’t always keep the major festivities going for the whole 2 weeks, traditionally Chinese New Year has always lasted a full lunar cycle, or approximately 15 days. Instead, they may choose to only hold significant celebrations on certain days. For example, Hokkien families typically host big gatherings on the 9th day, which also happens to be the Jade Emperor’s birthday, to commemorate their rescue from bandits by the Jade Emperor according to folklore. Each day of Chinese New Year holds a special significance with their own unique symbolisms and practices. And while there’s no strict adherence to dated customs, a little nugget of information here and there never hurt anyone.

How do Malaysians celebrate Chinese New Year?

Needless to say, Chinese New Year is the token Chinese celebration not only for those who reside in Mainland China, but among the various derivative sub-dialect groups that have already migrated over and planted their roots in foreign lands such as Malaysia. And while many parallels can be drawn between certain customs and practices, there are some that are just so uniquely Malaysian that it’s safe to say they aren’t seen anywhere else. Let’s go over some of them now.

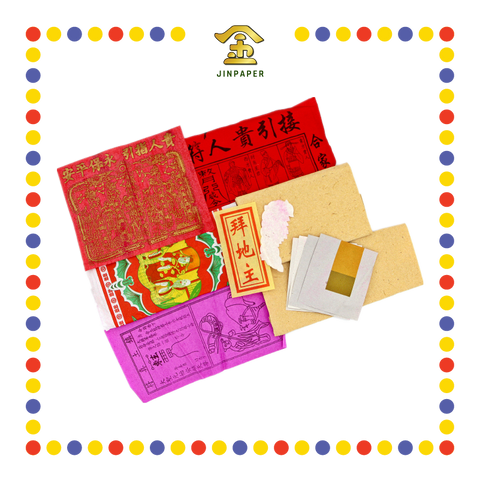

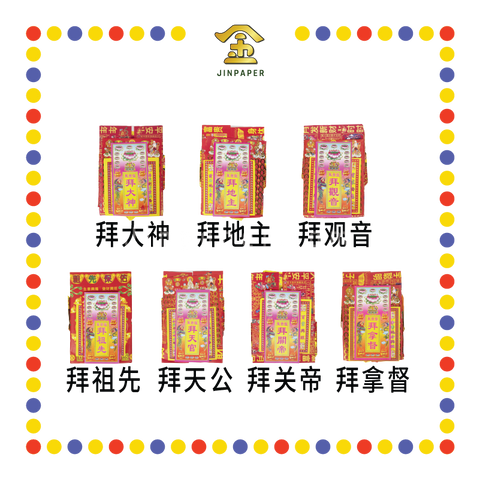

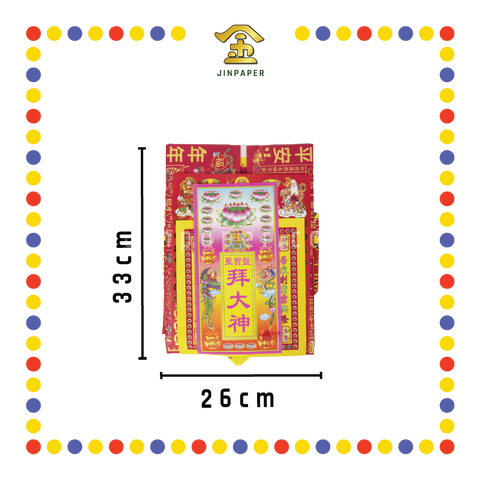

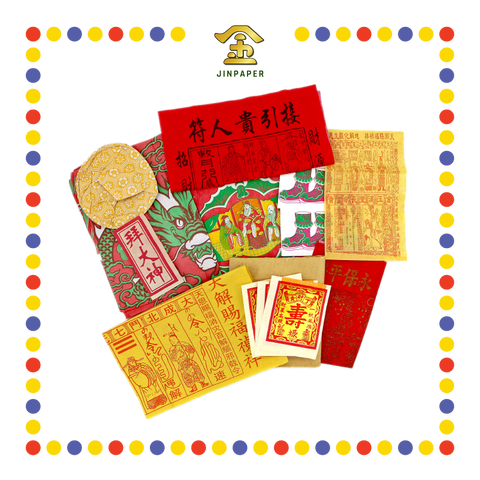

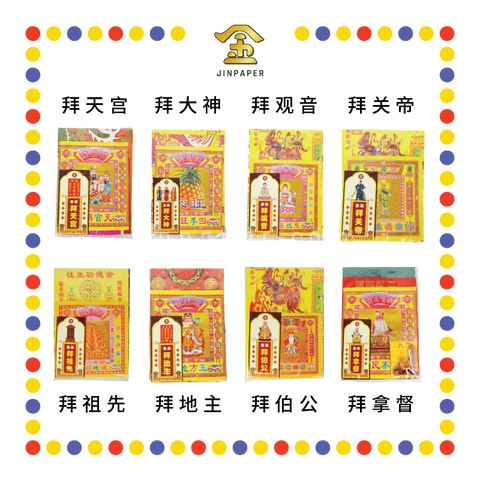

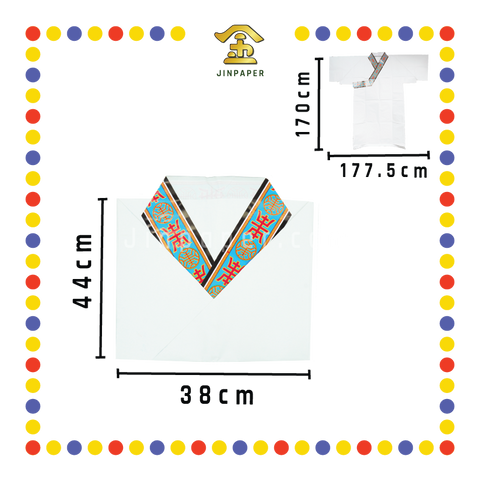

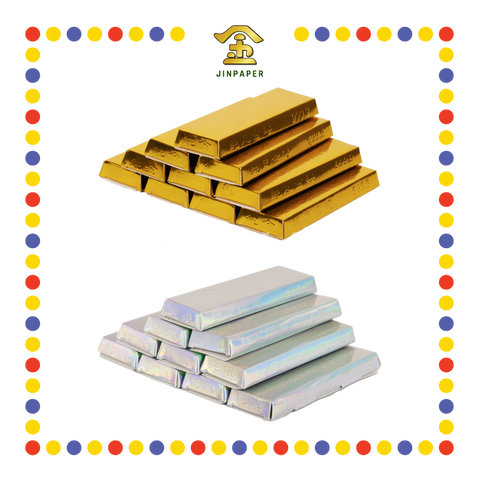

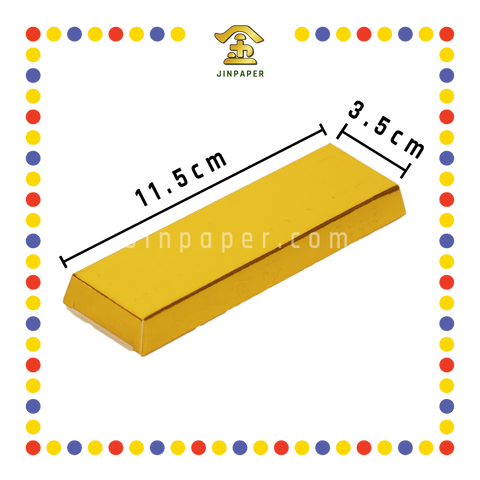

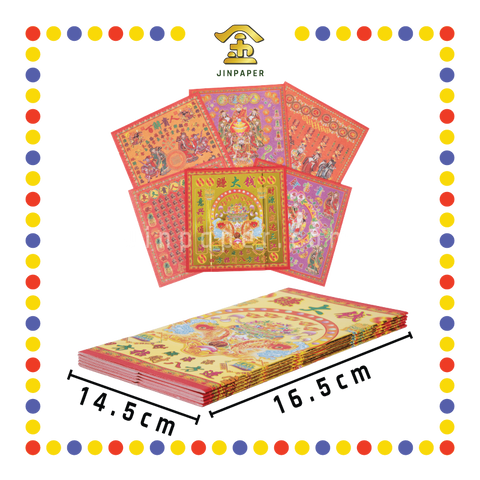

Any good start to Chinese New Year festivities hinges greatly on the preparation, which typically begins long before the day itself. Prep work takes up a sizable chunk of time and focus to accomplish well, and not without good reason. Families would often use this time to clean their house, throwing out old and broken household items they no longer need and replacing them with new ones. Some families even make it customary to purchase a new set of clothes to wear during this time of year. The house itself would also be decorated with an array of red paper decorations and many other festive baubles. Aside from which, families may also have to stock up on prayer supplies such as incense and joss paper, as well as food offerings such as pastries and fruits.

Aside from all the cleaning and decorating, no Chinese New Year celebration is complete without an adequately luxurious menu. It is no exaggeration to say that much of the preparation thus far was to build up to the reunion feast on Chinese New Year’s Eve. Families would gather under one roof and dine together, catching up on recent happenings and old memories all the same. This is the time when all your closest and dearest are together with you, and what better way is there to start the new year? There are no specific rules as to what should go on the dining table during a reunion dinner, however some do make it a family tradition to put up specific dishes, oftentimes to symbolize prosperity. Fish are a popular example, as it is believed that fish (鱼 / Yú) represents a surplus (余 / Yú) in fortune or wealth, due to its phonetic resemblance to the term in Mandarin. On the other hand, some modern families prefer to adopt a more carefree approach in the style of potlucks, whereby each family can choose to bring whichever dishes they want. Catering is a viable option as well.

First day of Chinese New Year is always the most happening. Early in the morning, family members would gather together and visit relatives by order of seniority. While not customary, some would also visit temples and light up large dragon joss sticks as well as firecrackers to start the day. The younger generation would also receive the red packets containing money from the adults and some of their older peers, as a token of blessing. To invite even more good fortune, families may opt to hire lion and dragon dance performers to their houses as well. Children are usually rather fond of these performances, and are often encouraged to ‘feed’ the lion by holding a mandarin orange into its mouth.

One unique practice amongst Chinese Malaysians however, is the lousang, otherwise known as the Prosperity Toss, a Cantonese-style raw fish salad that is said to have originated from Guangdong, China. Not much else is mentioned with regards to its origins however, as the dish today is consumed very differently than how it’s normally served back in China, so much so that it has become a trademark Malaysian custom altogether. The dish consists of numerous ingredients, each symbolizing an aspect of prosperity, such as fish, pomelo, carrots, radish, crushed peanuts, and sesame seeds. The practice of eating it will require some dexterity, as once everyone is gathered around the dish, they would need to use their chopsticks to toss the salad high into the air whilst verbalizing any auspicious wishes they wish to say. Lohei (撈起), or scoop up, is a common phrase to shout while tossing lousang.

Lousang, a Cantonese raw fish salad served during Chinese New Year. Source: JinPaper

Conclusion

Chinese New Year is a tradition that is steeped in much history and culture. There is much we can glean from its beginnings in history when sacrificial rituals were still commonplace, to its origins in folklore with tales of the infamous Nian beast. Certain practices have withstood the test of time and are staunchly guarded to this day, while others have grown and adapted with modern society and locality. But one thing is for certain, the significance of this once-in-a-year celebration holds true for its people now, and will continue to do so for the generations to come.

If you would like to see more posts about traditional Chinese customs and religious practices, be sure to check us out at JinPaper, Malaysia’s number one supplier for prayer supplies. And if there’s anything we missed out that you would like to see featured, leave us a note in the comments below!