How to pray Datuk Gong Malaysia

How to pray Datuk Gong Malaysia | Na Tuk Kong Birthday

If the name of this custom sounds at all Malay to you, that’s because for the most part, it is. Largely celebrated by Chinese ethnic groups throughout Southeast Asia, particularly those residing in Singapore, Malaysia, and certain parts of Indonesia, Datuk Kong worship involves praying to the spirit that inhabits the land and protects its worshippers.

Owing much to the cultural diversity of the region, the spirit goes by many names, but is most often simply referred to as Datuk Kong or Dato Keramat in Malay, and Na Tuk Kong or La Tuk Kong in Chinese. It should be noted that these all refer to the same entity, and the meaning behind them are more or less the same. While sometimes also used as an honorific title, Datuk or Dato means grandfather in the Malay language, and Na Tuk or La Tuk is simply the Chinese translation for it. Kong or Gong is also a Chinese word for grandfather.

History of Datuk Kong

Contrary to other Chinese customs, it hadn’t been that long since worship of Datuk Kong began. The earliest the practice dates back to is some time around the 19th century, when Southeast Asia started seeing an influx of Chinese migrants due to the industrial boom. It is believed that when the Chinese tried to explain their culture of praying to the Tu Di Gong to ask for protection, they pronounced it as ‘tok kong’, which the local Malay population then interpreted as Datuk Gong/Kong.

Prior to the arrival of Chinese migrants, local Malays had a practice of worshipping guardian deities of the land as well, which are thought to reside in ‘unusual’ natural formations like an oddly shaped rock or a large tree. Eventually, when the Chinese started settling down in the region, the custom of worshipping Tu Di Gong slowly merged with the local practices to become the Datuk Kong we know today.

Statue of a Datuk, garbed in a Malay sarong and wearing a songkok. Source: JinPaper

Similar to how the title of Datuk or Dato is conferred upon an individual who has made significant contributions to the people, the Datuk Kong refers to the collective ‘Datuks’ who have accomplished great deeds for civilization and society in the time that they were alive. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they possessed a Datuk title in life, but rather that each of them in their own right, was a hallmark of human virtue. The keramat that is in the Malay version of the name is also an Arabic term representing sacredness and glory, exemplifying the magnanimity that the spirit is believed to possess.

Some believe that fundamentally there are nine types of Datuks, and barring the last Datuk, each was a powerful warrior and expert practitioner of the silat, the local Malay martial arts. They are also believed to possess magical abilities.

Over the years however, as it can sometimes be seen as controversial to conventional Islamic customs, authorities have taken a more restrictive approach towards curbing the practice, and it is no longer as common among Malays and Indian Muslims. That being said, Datuk Kong worship had already taken root within the Chinese communities by then, and thus managed to live on till today.

Why Do Malaysians Pray to Datuk Kong?

Although Datuk Kong, or Dato Kong as some may call it, generally refers to the local guardian spirit of the land, it should be noted that each Dato is an individual in its own right, and that they all have unique temperaments that should be accounted for during worship.

In Malaysia, when travelling down the countryside, one may often stumble upon a yellow-painted shrine sitting next to the road. These shrines are known as keramat, and are highly representative of the Chinese-Muslim influence that Dato Kong worship is known for. Within the shrines themselves, there would sometimes be either a small statue or a stone wrapped in yellow cloth, representing the Dato.

Dato Kong worship is known to grant different effects, depending on the individual Dato that you’re praying to. For that, Dato worship can sometimes be seen as an alternative avenue for spiritual healing and protection. Spiritual mediums, more commonly known as bomohs, would channel these entities and enter into a trance prior to a consultation session. Worshippers would then be able to communicate with the Dato through the medium and ask for blessings, cures for illnesses, lottery predictions and just general guidance with overcoming certain obstacles in life.

When to Pray to Datuk Kong?

There are no set dates for Datuk Kong worship, but as mentioned before, each Datuk is an individual, and for that reason they each have different feast days. Certain rituals and offerings may also differ depending on the Datuk being worshipped. There are often folk tales speaking of how Datuks would appear in one’s dreams and beseeching them to erect shrines and give worship three times a day; once before sunrise, once at sundown, and lastly, once in the evening. Special offerings would also be presented on the 1st and 15th day of each lunar month.

While the Malay demographic is dwindling among worshippers in recent years, it was said that they normally performed their rituals on Mondays and Fridays. Some, on the other hand, have said that it was better to perform it on Thursday evenings instead, as it is believed that Datuks help to chase away evil spirits who try to dissuade Malay Muslims from participating in the Friday prayers that happen the following day.

How to Pray to Datuk Kong?

To normal Malaysian Chinese households, the Datuk Kong is simply viewed as the local guardian deity of the land, residing in trees, ant hills, strange rock formations, and the like. For most, Datuk worship begins soon after one receives a vision of the entity’s spiritual presence. It is believed that the Datuk Kong commonly appears in the form of a white tiger or an old man dressed in white. Readers should also note that while Datuk Kong can be “invited” into one’s house for protection and good fortune, they must never be allowed to reside within the house itself.

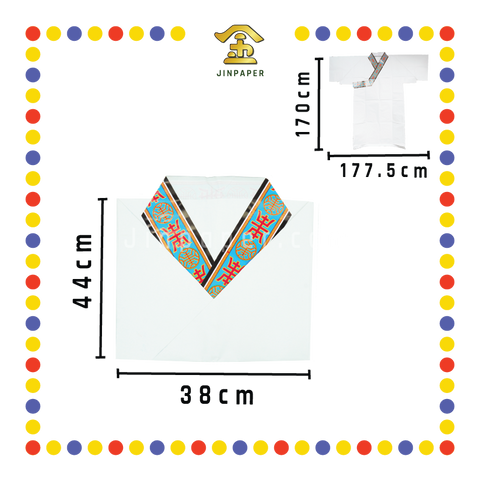

Likely as a result of the regional culture and local mainstream influences, the Datuk Kong is often depicted differently from one another. For some, the Datuk Kong is portrayed through an idol or a figurine; for others, it can be as simple as a tablet with his title inscribed upon the surface, a rock wrapped in yellow cloth, a songkok, a stack of incense, or even just flags. The shrine itself would often be adorned with Malay-themed items, such as a keris, a rattan cane, and baju Melayu, denoting the Datuk Kong’s position as a Malay guardian, and that he is fundamentally different from the conventional Chinese deities that are commonly worshipped.

A Datuk Kong is not bound by race, as Siamese, Indian and Orang Asli Datuks can be worshipped as such. Each Datuk Kong may also serve a different function and possess a certain type of influence depending on the community they reside in. However, for the sake of clarity, it is best to just think of them as the protector spirits of the local populace. When it comes to temples, a Datuk Kong shrine is normally placed outside of the main building, and only for temples which primarily worship the spirit will its idol be enshrined within the main altar.

As mentioned previously, one can worship Datuk Kong at any day of the week. Conventional offerings include a pair of white candles, 3 joss sticks, as well as the burning of gum benjamin (kemenyan). Besides fruits and the basic offerings, worshippers will also prepare a relatively more luxurious spread on Thursday evenings. These typically consist of a set of betel nut leaves complete with lime (kapur), sliced betel nuts (pinang), Javanese tobacco (tembakau Jawa), and palm cigarette leaves (rokok daun).

To reiterate, depending on the region you reside in, there may be certain practices when worshipping Datuk Kong that differ from other places. For example, in the northern regions of Malaysia such as Perlis, Kedah, and Penang, worshippers would slaughter chickens to be used in the kenduri, or feast. Sometimes, goats would be used as well. It is important to note that the butchering must be performed by a Muslim, as the meat offerings must be halal before it can be presented to the Datuk. Pork meat is considered unclean and is thus avoided during worship. As is often practiced in Malay feasts, turmeric rice (nasi kunyit) is presented as an offering to the Datuk, along with a curry dish that’s prepared using the meat from the slaughter. Albeit so, given that the Chinese form a majority of the worshipper demographic, it is fairly common to find Chinese dishes served as normally seen in other Chinese religious practices.

Aside from food offerings, worshippers can also sometimes present fresh flowers, betel nut leaves (sirih), and locally-made hand-rolled cigarettes (rokok daun). Sliced areca nuts (pinang) and local fruits also make for a popular offering.

A crucial step in the Datuk Kong worship ritual is the burning of gum benjamin. This is commonly sourced from local gum trees, and emits a smoky fragrance when burnt. Should the worshippers’ prayers be answered, they would usually come back to the shrine to make offerings and sometimes organize feasts in gratitude. Such feasts would often consist of yellow saffron rice, either lamb or chicken curry, an assortment of vegetables, local bananas (pisang rastali), young coconuts, rose syrup, local cigars (cherrots) and local fruits. When worshippers consider their patron Datuks to be highly influential and powerful, they would also often put in renovations for the local shrine to make it more beautiful and grander-looking. Visitors would also be requested to not be disrespectful when inside or around the vicinity of the shrine.

A Datuk Kong shrine. Source: JinPaper

Conclusion

Hopefully, you found this short read enlightening, as Datuk Kong worship is understandably not as widespread outside of Southeast Asia. However, obscure as it may be, the practice does live on, and if you ever intend to pay respects, please do find out which Datuk Kong you are praying to and take note of the do’s and don’ts when doing so.

For more topics on Chinese customs and prayers, check us out at JinPaper, your number one source for prayer items and supplies! If you’d like to see more unique customs being featured, be sure to let us know in the comments below!